From Spit to Slaughter: The Escalatory Logic of Antisemitism

My essay traces how street-level harassment of Jewish children—from Vienna to Białystok to London—has repeatedly paved the way for organised violence.

In the Schoolyard Before the Pogrom: A Pattern Repeats

Understanding why the targeting of Jewish children is key to recognising—and halting—the early stages of escalating antisemitic violence in contemporary Britain.

Antisemitism does not erupt overnight—it escalates. What begins as street harassment of visibly Jewish children often lays the groundwork for broader social acceptance of exclusion, intimidation, and eventually violence. This paper traces that progression across historical case studies—from fin-de-siècle Vienna and Wilhelmine Germany to Eastern Europe under Imperial Russia—before turning to present-day incidents in Britain and Israel. By mapping how societies normalize antisemitism through everyday targeting of children, I argue that early-stage harassment is not incidental but foundational to systemic violence. Recognizing these patterns is vital for breaking the cycle.

From Street Harassment to Violence: The Escalatory Pattern of Antisemitism

The path from casual harassment to systematic violence rarely begins with dramatic acts of hatred. Instead, it starts with what seems ordinary: children mocked on their way to school, adults jeered in the street, communities made to feel unwelcome in public spaces. Yet history reveals a disturbing truth—what begins as "mere" harassment of Jewish adults and children has a worrying propensity for escalation, creating the social conditions that enable far worse atrocities.

This pattern, documented across continents and centuries, demands our attention not merely as historical curiosity, but as urgent warning. From the streets of fin-de-siècle Vienna to contemporary British neighbourhoods, the normalization of antisemitic harassment has repeatedly served as prelude to violence. Understanding this progression—and recognizing its contemporary manifestations—becomes essential for preventing its tragic endpoints.

Historical Foundations: When Harassment Becomes Acceptable (1870s-1900s)

Vienna's Institutionalized Hostility

Turn-of-the-century Vienna under Karl Lueger's antisemitic mayorship provides a chilling case study in how political permission translates to street-level harassment. Jewish children walking to school became routine targets, regularly spat at, mocked, and physically harassed by both peers and adults. This wasn't random cruelty—it was systematic targeting enabled by official attitudes.

Stefan Zweig, in his memoir The World of Yesterday, recalls the transformation of his beloved Vienna into a place where antisemitic hostility became not just acceptable, but fashionable. The Nobel laureate witnessed how quickly social norms could shift, making Jewish children particularly vulnerable as both symbolic and literal targets of a society's changing values. By 1933, addressing an audience about the spread of these patterns beyond Austria, Zweig captured the psychological devastation with haunting precision:

"Think of the fate prepared for thousands of German children today, through organized humiliation. A little girl wants to play with other children; but they shrink from her, hurl an ugly word at her … the memory of the scoffing of the other children … remains." (Zweig, 1933)1

What makes Zweig's testimony particularly powerful is how it demonstrates that harassment creates lasting trauma. The "memory... remains"—embedding itself in the consciousness of a child, long after the immediate incident ends. This psychological scarring became a deliberate tool of exclusion and dehumanization.

Carl E. Schorske's research in Fin-de-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture explores how figures such as Georg von Schönerer and Karl Lueger shaped Viennese antisemitism through populist mass politics, appealing broadly to the middle class. It maps how antisemitism became culturally legitimized and politically effective in public life2.

Lueger used symbolic and institutional channels—like schools and youth events—to cultivate loyalty among children, portraying himself as a paternal guardian for Vienna’s Christian youth. Children were subtly incorporated into a broader cultural environment shaped by antisemitic propaganda and political ritualism.

Schorske's research reveals, therefore, how antisemitic organizations and individuals deliberately targeted Jewish children as part of their ideological training, teaching young Austrians that harassment of Jewish peers was not only acceptable but necessary. Children became both perpetrators and victims in a cycle designed to normalize hatred.

German States: The Racialization of Daily Life

The rise of Wilhelm Marr's racial antisemitism across German states created similar conditions. In 1879, the German writer Marr introduced the term ‘antisemitism’ originally meaning to "impart a new, nonreligious connotation to the term anti-Jewish" but, within a short period it became "popular specifically among writers and scholars . . . because of it's scientific pretensions (as well as the) uncertainty over the intent (of the user) of hatred of the Jews."3

In the same year, Marr also introduced the idea that Germans and Jews were locked in a longstanding conflict with ‘Germanic peoples’, the origins of which he attributed to race—and that the Jews were winning4.

As a consequence, Jewish children in Berlin, Breslau, and Königsberg faced what Jacob Katz's authoritative research highlights5 as daily verbal abuse, physical harassment, and segregation both in schools and public spaces when commuting—part of what Katz identified as a structured culture of antisemitism across mixed-religion urban settings.

The account of Rudolf Schmerl, born in August 1930 outside of Berlin, Germany, describes his family; moving to Berlin in 1935. His first-hand account is illustrative of how Jewish children were subjected to taunts and slurs, and subjected to threats of - and actual - physical violence, simply for being identifiably Jewish in public spaces.

“What I remember specifically is being terrified and running, and a gang of boys-- looking back, obviously little boys, but at the time they seemed like big boys-- chasing me and calling me names and--”

[Interviewer: What kind of names were they calling you?]

“"Judenschwein"-- "Jewish pig."

[Interviewer: So it was because you were Jewish, then--]

“Of course. Yes”6 (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, n.d.)

What makes Schmerl’s first-hand account of being taunted in public space particularly disturbing is that all similar accounts are remarkable for their ordinariness. These weren't isolated attacks by extremist groups, but daily experiences woven into the fabric of community life for Jewish people growing up.

Parents knew their children faced harassment; teachers often ignored it; neighbours frequently encouraged it. The systematic nature of this treatment reveals how quickly entire communities can normalize the targeting of vulnerable populations.

Eastern European Experiences: Confined and Targeted

In Russian-controlled Poland, the Pale of Settlement concentrated Jewish populations, making them highly visible targets for harassment. Jewish children attending cheders (religious schools) in cities like Białystok, Kraków, and Warsaw regularly faced attacks by Polish and Russian children who threw stones, shouted insults, and attempted to tear their religious clothing.

Isaac Bashevis Singer provides particularly vivid testimony in his autobiographical work In My Father's Court. The Nobel laureate recounts how Jews—including children—were routinely jeered and harassed in the streets of Warsaw and Bilgoraj. Singer grew up on Warsaw's impoverished Krochmalna Street, "a world shaped by communal poverty, pervasive antisemitism, and humiliating control by local gentile power structures."7 These weren't exceptional events but part of daily life, creating an atmosphere of constant intimidation for Jewish families.

The progression from harassment to violence becomes starkly evident in the lead-up to the 1906 Białystok pogrom, which incapsulated the broader context of violence and persecution faced by Jews during this time8. Prior to the eruption of the deadly Bialystok pogrom violence, there had been steadily rising reports of hostile street harassment targeting young Jews on their way to school. The pogrom, which ultimately claimed many victims including children9, didn't emerge from nowhere—it was the culmination of months of escalating street-level intimidation.

Historian Ezra Mendelsohn, in The Jews of East Central Europe Between the World Wars, documents how this harassment extended into educational institutions themselves, with Jewish children facing systematic exclusion and abuse within Polish schools. The message was clear: Jewish children were unwelcome in public spaces, whether on the street or in classrooms.

Imperial Russia: The Impossible Choices

Pauline Wengeroff's memoirs provide crucial insight into how harassment created impossible choices for Jewish families throughout the Russian Empire. Born in 1833 and dying in 1916, Wengeroff witnessed the entire arc from relative acceptance to systematic persecution, making her testimony particularly valuable for understanding escalation patterns.

Her account of her son Simon's experience at gymnasium reveals how harassment moved from streets into institutional settings:

"Simon was a fourth grade student. The students were taken to the chapel for religious services. All but Simon kneeled before the icons. When the teacher ordered him to kneel, he refused: 'I am a Jew. My religion forbids me to kneel to an image.' After the service, the enraged teacher told Simon he was expelled."10 (Bernstein, 2014, p. 16)

The targeting wasn't limited to religious observance. When her other son, Volodya, applied to university with excellent grades, the admissions clerk rejected his papers outright:

"These are not your papers, you must have stolen them. You are a Jew, but these papers refer to someone with a Russian name—Vladimir."11 (Bernstein, 2014, p. 25)

Only after converting to Christianity was Volodya immediately accepted.

Wengeroff documented the rapid transformation of Russian society: "An academic education became more and more difficult for Jews to attain, for only a very small Jewish quota was admitted to the gymnasiums and even fewer were admitted to universities." The relatively tolerant period under Alexander II ended abruptly with his assassination in 1881, after which "antisemitism erupted; the Jews were forced back into the ghetto."

Most significantly, Wengeroff witnessed the coining of a new word: "Pogrom was a new word, coined in the eighties. The Jews of Kiev, Romny, Konotop, were among the first to experience the savage assault of the local mobs." (Bernstein, 2014, p.25) Her memoir demonstrates how systematic harassment created the social conditions that made organized violence not just possible, but inevitable.

Identifying the Pattern: Common Elements Across Time and Place

Examining these historical cases reveals consistent elements that transcend geographic and temporal boundaries. Jewish children were typically identified by distinctive clothing, haircuts, or schoolbooks that marked them as targets. The harassment followed predictable escalation patterns: verbal abuse leading to physical intimidation, individual targeting expanding to group attacks, and isolated incidents becoming systematic campaigns.

The behaviours themselves remained remarkably consistent across different countries and decades: stone throwing, name-calling, pushing and shoving, mockery of religious symbols, and attempts to forcibly remove yarmulkes or tzitzit. Perhaps most troubling, this behaviour was rarely punished and often encouraged by parents, teachers, and local clergy who viewed it as acceptable expression of community sentiment.

Social permission proved crucial. When authority figures signal that harassment is acceptable—whether through official policies, religious teachings, or simple inaction—communities quickly internalize these messages. Children learn not just to tolerate harassment of Jewish peers, but to participate in it as a form of social belonging.

Institutional complicity emerged as a key factor. Wengeroff's experiences show how schools, universities, and government offices became sites where Jewish identity itself became grounds for exclusion or forced conversion. The systematic nature of this discrimination created what she called impossible choices: "In the eighties, with antisemitism raging all over Russia, a Jew had two choices. He could, in the name of Judaism, renounce everything that has become indispensable to him, or he could choose freedom, with its offers of education and career, through baptism."

Contemporary Echoes: Digital and Physical Harassment (2023-2025)

The historical patterns haven't disappeared—they've evolved for the digital age while maintaining their essential characteristics. Contemporary examples reveal the same progression from acceptable discourse to physical intimidation, with October 7th, 2023, serving as a particular inflection point for normalized antisemitic expression.

Academic Antisemitism: The El Kadmiri Case

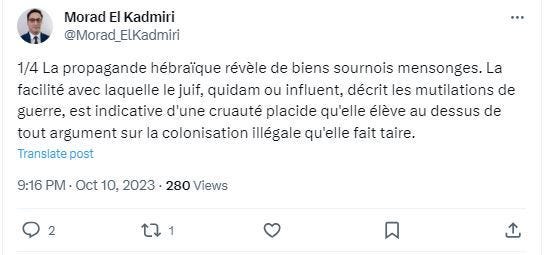

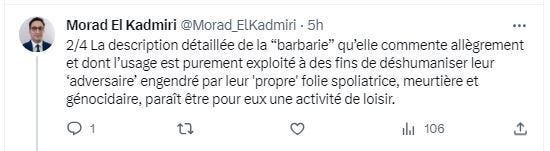

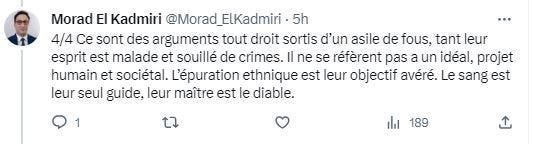

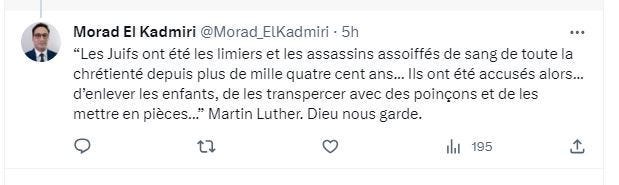

Dr. Morad El Kadmiri, who has taught at prestigious institutions including Essex, Warwick, and UCL, exemplifies how intellectual positions provide contemporary cover for dehumanizing rhetoric. Days after the October 7th Hamas attacks, El Kadmiri posted - on the 10th of October - a series of tweets that echo historical antisemitic tropes while claiming academic legitimacy. Something I noted, and recorded the evidence of at the time.

In his posts, he wrote: "Hebrew propaganda reveals very devious lies. The ease with which the Jew, whether ordinary or influential, describes the mutilations of war, is indicative of a placid cruelty that it elevates above any argument about illegal colonization that it silences."

He continued: "The detailed description of the 'barbarism' which she blithely comments on and whose use is purely exploited for the purpose of dehumanizing their 'adversary' engendered by their 'own' despoliatory, murderous and genocidal madness, seems to be a leisure activity for them."

Most disturbing was his conclusion: "These are arguments straight out of an insane asylum, so sick and soiled are their minds with crimes... Ethnic cleansing is their proven goal. Blood is their only guide, their master is the devil."

The final post invoked blood libel explicitly: "The Jews have been the first and the assassins thirsty for blood of all the Christians for a thousand four hundred years... They have been accused of kidnapping children, of piercing them with swords and putting them in pieces... Martin Luther. God keep us."

El Kadmiri's language—attributing collective guilt, invoking blood libel imagery, characterizing Jews as inherently deceptive and cruel—directly parallels the rhetoric used to justify historical harassment of Jewish communities. The academic credentials provide a veneer of respectability to ideas that would have been familiar to Wilhelm Marr or Karl Lueger.

Most significantly, El Kadmiri's posts went largely unchallenged by his academic institutions, suggesting the same social permission that enabled historical harassment. When respected academics can publicly dehumanize Jews without professional consequences, it signals to broader society that such attitudes are acceptable.

Street-Level Intimidation: UK Water Gun Incident

On August 3, 2025, in the UK, two men filmed themselves driving through a Jewish neighbourhood in London, spraying Orthodox Jews with water guns while laughing and recording their victims' reactions.

One perpetrator was identified as Kamil Galanty, a UK resident originally from Poland. The men specifically targeted individuals whose religious clothing made them identifiably Jewish—the same targeting method used by harassers in historical cases.

The incident reveals several troubling patterns. The perpetrators filmed their actions for social media distribution, suggesting they expected approval rather than condemnation from their online communities. They chose a predominantly Jewish neighbourhood, indicating premeditation and systematic targeting. Most disturbing, they treated the harassment of Jewish children as entertainment, laughing throughout the attacks.

One hears afresh Stefan Zweig’s 1933 comments about “the memory…remains”.

The cross-cultural nature of the perpetrators—Polish nationals living in Britain targeting British Jews—demonstrates how antisemitic harassment transcends specific national or cultural contexts. Galanty brought attitudes from one country to another, finding them readily applicable to local Jewish communities.

Verbal Escalation: Glasgow Holocaust Threats

In Glasgow, in the immediate days following October 7th, a young girl was recorded shouting “Free Palestine” while menacingly telling Jewish individuals to “don’t forget where you were in 1940. Don’t forget where the Jews were in 1941”—explicitly invoking historical genocide as a threat against contemporary Jews. I secured the video evidence of the incident from the social media storm in the immediate aftermath of the Hamas pogrom.

This incident demonstrates how children inherit and amplify antisemitic messages, while the invocation of the Holocaust shows how historical trauma becomes weaponized against victims' descendants.

The girl's conflation of “Free Palestine” rhetoric with Holocaust threats reveals how political slogans can serve as cover for antisemitic expression. This mirrors historical patterns where legitimate political grievances became pretexts for targeting Jewish communities who had no connection to the underlying disputes.

The incident particularly echoes Wengeroff's observation about children growing up “without the memories of Judaism” but with full exposure to antisemitic messaging. Just as she witnessed Russian children learning to target Jewish peers as a form of social belonging, contemporary children learn to weaponize historical trauma against Jewish communities in the UK today.

The Ultimate Escalation: October 7th and the Idan Family Tragedy

The October 7th Hamas attacks represent the logical endpoint of unchecked antisemitic harassment culture—the transformation of systematic dehumanization into organized violence. The tragedy of the Idan family exemplifies how abstract hatred becomes personal devastation.

Tsahi Idan, his wife Gali, and their children were among the victims of attacks that specifically targeted Jewish families in their homes. The perpetrators didn't distinguish between combatants and civilians, adults and children, or individuals with any particular political views—they targeted people for being Jewish, just as historical pogroms targeted entire communities regardless of individuals' actions or beliefs.

Hamas terrorists broke into their home, murdered the eldest daughter by shooting through the door of their safe room. The proceeded to livestream the terrorising of the family live via their Facebook account. (Times of Israel Staff, 2025)

The attacks weren't spontaneous explosions of anger but carefully planned operations that built upon decades of rhetoric dehumanizing Jewish people. The same language patterns visible in historical antisemitism—portraying Jews as inherently evil, collectively responsible for various grievances, deserving of violence—provided ideological justification for targeting families like the Idans.

Tragically, the father in the footage - Tsahi Idan - would be taken as a hostage. He did not survive.12

Hamas's own statements and training materials reveal how systematic dehumanization prepares perpetrators for violence. By teaching that Jewish people are inherently evil and dangerous, the organization created conditions where attacking children becomes not just permissible but necessary. This represents the complete realization of what begins with "harmless" harassment in school yards and neighbourhoods.

The progression is clear: from El Kadmiri's academic dehumanization to Galanty's street-level intimidation to the Glasgow girl's Holocaust threats to Hamas's organized violence. Each step builds upon the previous one, creating social permission for increasingly extreme targeting of Jewish individuals and communities.

Breaking the Cycle: Recognition and Response

The pattern is unmistakable: what begins as socially acceptable harassment of Jewish individuals—particularly children—creates conditions for systematic violence. Each historical case study reveals the same progression from verbal abuse to physical intimidation to organized attacks. Contemporary examples suggest this cycle continues, adapting to new technologies and political contexts while maintaining its essential character.

Wengeroff's memoir provides perhaps the most crucial insight: these transformations happen quickly and often surprise those who experience them. She witnessed Russian society move from relative tolerance to systematic persecution within a single generation. Her "wise mother" predicted this trajectory: "Two things I know for certain. I and my generation will surely live and die as Jews. Our grandchildren will surely live and die not as Jews. But what our children will be I cannot foresee."

The middle generation—caught between acceptance and persecution—faced impossible choices that contemporary Jewish communities increasingly recognize. Wengeroff's documentation of how harassment created social pressure for conversion or assimilation provides crucial historical context for understanding modern dynamics.

Recognition of these patterns demands response at multiple levels. Educational institutions must address harassment in its earliest forms rather than tolerating it as acceptable expression. Social media platforms must recognize that dehumanizing rhetoric against any group creates conditions for real-world violence. Political leaders must understand that normalized harassment serves as early warning system for potential atrocities.

Perhaps most importantly, communities must reject the false comfort of treating harassment as merely unfortunate but inevitable. History demonstrates repeatedly that societies have choices about what behaviors they normalize and what values they enforce. When harassment becomes acceptable, violence becomes possible. When violence becomes possible, tragedies like October 7th become probable.

The voices of survivors like Stefan Zweig, Isaac Bashevis Singer, and Pauline Wengeroff remind us that these patterns are neither mysterious nor inevitable. They result from human choices—to participate, to permit, or to prevent. The question facing contemporary societies isn't whether antisemitic harassment will continue, but whether we'll recognize it early enough to stop its escalation.

Zweig's 1933 warning about children who face "organized humiliation" resonates across the decades. The "memory of the scoffing" doesn't fade—it accumulates, creating social conditions where targeting Jewish individuals becomes normalized. Understanding this progression from harassment to violence isn't merely academic exercise—it's moral imperative.

The children walking to school in Vienna, Berlin, Warsaw, and St. Petersburg deserved protection their societies failed to provide. Contemporary Jewish communities deserve better. History offers the roadmap; the choice to follow it remains ours.

Dean M Thomson is currently a lecturer with Beijing Normal - Baptist University (BNBU), formerly known as Beijing Normal - Hong Kong Baptist University, United International College (UIC).

My work is entirely reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber

Alternatively why not make a one-off donation? All support is appreciated

Why not read and listen to more material?

Five Types of Anti-Zionism: A Logic Test for Antisemitism

After two Jews were murdered in a Manchester synagogue, activists took to the streets—not in solidarity, but in protest. We urgently need to identify when anti-Zionism crosses into antisemitism. Using logical syllogism, we can distinguish legitimate criticism of Israeli policy from the eliminationist antisemitism that followed October 3rd’s terrorist at…

So, I was on Untribal Podcast...

Just a heads-up that I was invited by the good people at Untribal Podcast earlier today to discuss the Israel-Palestine conflict, to withdraw heat and focus on illumination regarding the unfolding human catastrophe.

Zweig, S. (1933, December 28). Address to the Women’s Committee of the Central British Fund for German Jewry. As cited in Jewish Telegraphic Agency. https://www.jta.org/archive/stefan-zweig-depicts-humiliating-lives-of-german-jewish-children

Ross, A. (2015, September 28). The Schorske century. The New Yorker. Retrieved from https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/the-schorske-century

Zimmermann, M. (1986). Wilhelm Marr: The patriarch of antisemitism (D. Bronsen, Trans.). Oxford University Press.

Moshe Zimmermann Wilhem Marr: The Patriarch of Anti-Semitism, (New York, 1986) pp. 89, 95. It is worth noting that, according to Zimmermann, (p. 91) "the term antisemitism, which is considered by historians as an innovation in the transition from the religious basis of hatred of the Jews to the racial basis was not (emphasis in the original) so initially." Zimmermann also notes (p. 89, p. 167 n. 96) following Reinhard Rurup, that there had been other, incidental uses of the term antisemitism prior to 1879.

Marr, W. (1879). The victory of Judaism over Germandom (Trans. unknown). Retrieved from https://ghdi.ghi-dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=1797

Katz, J. (1980). From prejudice to destruction: Anti-Semitism, 1700–1933. Harvard University Press.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (n.d.). Oral history interview with Rudy Schmerl. Retrieved from https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn511105

Teatr NN. (n.d.). Isaac Bashevis Singer (1904-1991) - English version. Teatr NN Lexicon. Retrieved August 6, 2025, from https://teatrnn.pl/lexicon/articles/isaac-bashevis-singer-19041991-english-version/

Encyclopedia Britannica. (2025, July 25). Pogrom. https://www.britannica.com/topic/pogrom

"Report of the Duma Commission on the Bialystok Massacre". The American Jewish Year Book. 8: 84. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/23600501

Bernstein, D. (2014). Rav Kook in historical context: European society and the challenges of modernity. Elmad.pardes.org. Institute of Jewish Studies. https://elmad.pardes.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/ELS2014_BernsteinD_Kook_in_Historical_Context.pdf

Bernstein, D. (2014). Rav Kook in historical context: European society and the challenges of modernity. Elmad.pardes.org. Institute of Jewish Studies. https://elmad.pardes.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/ELS2014_BernsteinD_Kook_in_Historical_Context.pdf

Times of Israel Staff. (2025, February 27). Tsahi Idan’s family confirms his body has been identified after return from Gaza. The Times of Israel. Retrieved from https://www.timesofisrael.com/liveblog_entry/tsahi-idans-family-confirms-his-body-has-been-identified-after-return-from-gaza/