The English tradition of conservatism is shrivelling as Faragian populism takes hold

The left should be careful what it wishes for as the historic English tradition of conservatism shrivels up in the face of a tawdry populism.

My work is entirely reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber

Alternatively why not make a one-off donation? All support is appreciated

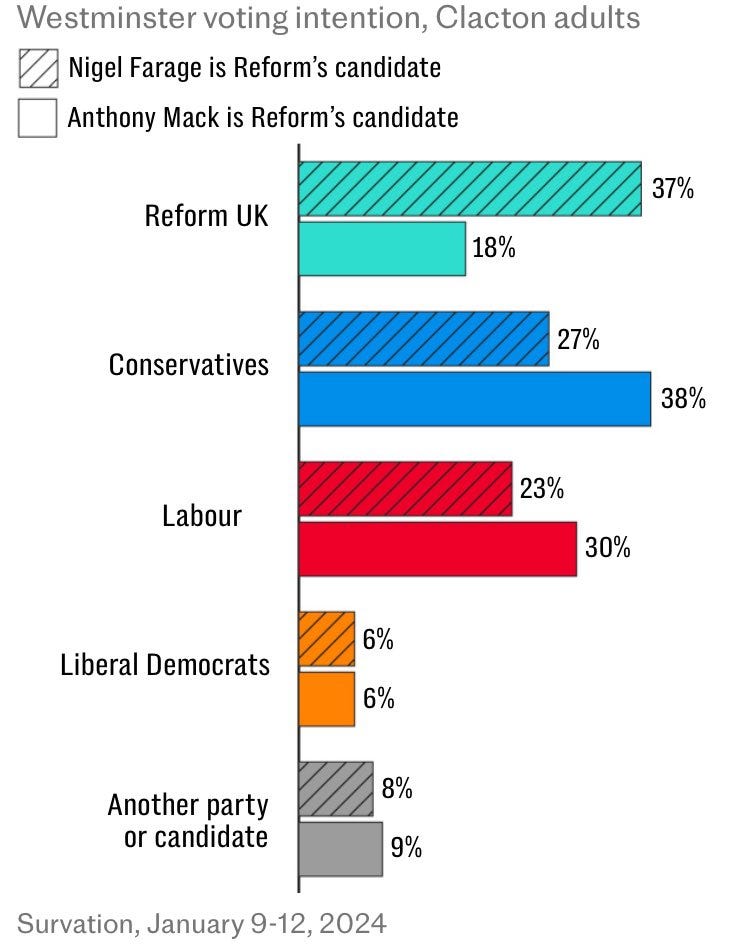

What does it mean to be a ‘conservative’? It might seem an odd question but the answer has existential consequences for the future of British politics, society and culture. As the Tories careen ever closer to 1997 variety disaster, Reform UK has appeared under the aegis of Nigel Farage. If current polling for Clacton holds, he’ll be in parliament. Farage as Banquo's ghost hovering over the ruins of the Conservative party. His influence over the surviving (likely populist) far right rump of the Tories risks becoming feverish. What does this mean for the conservative tradition which has helped insulate British politics from the worst excesses of the US culture wars?

Being conservative

When I lectured in China about ‘Anglo-American Society and Culture’, one of the hardest elements to communicate was the transatlantic conservative political tradition to a young Chinese undergraduate audience. They had no reference points at all to understand it.

After all, the English conservative tradition isn’t one where you can look back to ‘great thinkers’. This is a conservatism, there shouldn’t be any ‘great thinkers’.

Churchill once said ‘keep buggering on’, and it’s actually a useful guide to understanding the exceptionally old English conservative tradition. It’s a world where you keep buggering on, occasionally tinkering with the established parliamentary system to keep it humming along.

Tinkering and buggering on is not the grounds from which ‘great thinking’ ought emerge. At its core then, we’re talking about a political tradition not centred around personalities but long evolving habits, customs.

English conservatism is therefore reactive in a direct political sense, major action only in response to the threat of significant change. What it means to be a conservative in an English sense is therefore to look back to a literary heritage, reforming constantly tempered by a touching on the past. Glancing back in order to renew.

It all really starts with Judge Sir John Fortescue (1394-1479). Sir John’s lasting contribution was his comparison of the realm of England with France. He described a “dominium politicum et regale” (a political and royal dominion) of England as distinctive to the French “dominium regale” (a royal dominion).

For Fortescue, the Kingdom of England was where our sovereign could only make law and raise taxation with the consent of the realm via parliament. This is incredibly important, since the consequence of Sir John’s contribution is to root all future English conservatism in a parliamentary, constitutionalist and eventually democratic footing.

As an aside, if taken in this spirit we should really view the English civil war’s outcome as a victory for English conservatism. Parliamentarian forces striving to preserve (not overthrow) the “dominium politicum et regale”, from King Charles I who sought instead a foreign “dominium regale”.

Consider the key figures of English conservative tradition: Fortescue (judge), Sir Thomas Elyot (diplomat, scholar), Thomas Starkey (political theorist, humanist), John Alymer (Bishop of London, constitutionalist), Sir Thomas Smithg (scholar, parliamentarian). It’s a history spanning the 14th - 16th centuries. All of it representing a slowly emerging political culture. Each of these men referenced each other slowly over hundreds of years eventually constructing the foundations of English conservatism.

Thought anchored in place, specific times and culture. Foundationally focused on preserving traditions conceptualised around parliament, constitutional convention and individual liberty.

And that last point, liberty, demands we add in two other key figures: Locke and Burke. Without them English conservatism would merely have been focused on traditional institutions such as the biblical religion, the family, and the national state. But Locke and Burke introduce the alliance with liberalism thus resulting in an English conservatism which some (mistakenly) define as a classical liberalism.

What we see is a tradition which is favours limited government, property rights and individual liberty. But you shouldn’t mistake it for a classical liberalism in the truest sense. Unlike classical liberalism, it is empiricist and regards successful political arrangements as developing through an unceasing process of trial and error.

Ultimately, English conservatism retains a sceptical eye for claims about universal political truths. Remember, this is still ‘conservative’, rooted in place, specific times and culture. It is still focused on traditional institutions such as the biblical religion, the family, and the national state.

Thus we can answer ‘what does it mean to be conservative’ in the context of British (read: English) political culture. At least up until now. What depresses and alarms me deeply is that we are witnessing the demise of this fine old tradition.

What is set to replace it is the empty populism of Farage. A prospect which should fill my fellow Labour members with fright.

A political revolution

Nigel Farage opening pitch as he leapt into the General Election race as candidate and party leader is telling. For one thing, it’s immediately clear from his opening pitch he is foreign to the English conservative tradition.

His opening act was to vow to trigger a “political revolution”. In truly Trumpian terms he vowed to overthrow the political order, unveiling plans to abolish the House of Lords and overhaul the UK's voting system. Now many may say ‘good, what’s wrong with that?’ Hold on a minute chaps.

It is one thing for the Labour Party to say - rooted as it is in the narratives of British socialism - to seek to overturn said institutions. It’s quite another for a politician claiming to be part of the English conservative tradition to do so.

Nobody whose conservatism is rooted in the English tradition would pledge any of these things. To the politics of Nigel Farage, Sir John Fortescue’s “dominium politicum et regale” is something to be held in contempt.

Farage rallies his supporters against established constitutional traditions, wishes to smash “the elite”. Let’s be frank here, Reform UK isn’t part of any English conservatism at all, it’s Americanised Trumpian populism. And I for one fear the potential for it to become mainstreamed in our political system should the Tories be so defenestrated by Labour that the bubbling squabbling ruins of Tory rightists leap for Farage’s snake-oil.

In short, I’m deeply concerned English conservativism as a tradition is being replaced by an Americanised (and intellectually vacuous) populism.

Defining populism

Populism itself has a definition it would be prudent to lay out at this point.

Let’s begin with dispelling some intellectual fallacies. Populism isn’t the same thing as popular policy, nor is it a synonym for democracy. Populism is the manufacturing of a crude binary: ‘us’ vs ‘them’. Specifically, ‘us’ representing the ‘pure’ and ‘virtuous’ people pitied against ‘them’, a ‘corrupt’ and ‘degenerate’ elite.

Nigel Farage’s politics is entirely grounded in these terms. He rants endlessly about ‘us’ (his ‘peoples army’) locked in some sort of existential twilight struggle with ‘the mainstream media’ and ‘out of touch political class’.

The dishonesty is obvious, Farage himself is a career politician (MEP from 1999-2020). He was also a privately educated kid who worked in the City of London as a trader. He is about as much a part of this ‘out of touch political class’ as one could possibly get. See past the cigarette smoking, pint swirling bonhomie and what you see is a figure of, from and part of the socio-economic elite of the United Kingdom.

Further, when Farage decried the European Union as a corrupt distant elite against ‘us’ the ‘people’ he insisted that we should dismiss the experts. Amid calls to ‘take back control’, his Brexit appealed to a traditionalist sense of sovereignty where it should be horded within the confines of a border rather than pulled and shared supranationally. All justified through the false prism of a binary ‘us’ versus ‘them’ conceptualisation.

This intellectually vapid, clearly dishonest grifting self-serving bullshit is what we stand to see replace the fine old English conservative tradition after this General Election. Especially if polling proves correct and Farage worms his way into the Mother of all Parliaments.

Picture the scene, the Tories reduced to 1997 levels of MP, the rightists ready to drag their party ever-further away from the heritage which had made them great (one nation), all with Farage hovering over them.

He’d be there, licking his lips, slapping his thighs with glee - like Banquo's ghost. Touting his fears of foreigners on the one hand (with his fisher price binoculars, screaming about boats), and on the other an empty populist grift (the Labour party would be presented as the ‘them’, the ‘degenerate elite’). Instead a filthy, tawdry populism completely foreign to the English conservatism of our isles. You should be scared. Very scared. It’s a future coming to a town near you.

“To die, to sleep – to sleep, perchance to dream – ay, there's the rub, for in this sleep of death what dreams may come…”

Shakespeare had Hamlet think about all the inconvenient, tedious and unpleasant things about life and fantasises about ending them with a long sharp needle in the heart or brain. Right now, the Conservative Party might just opt to die, to sleep and perchance to dream…and opt to drink Farage’s poison.

Fortescue no more, Burke no more, Locke no more. The triumph of mediocrity, bigotry and racism over the narratives of English conservatism. It’s a deeply mournful moment we’re approaching.

My work is entirely reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber

Alternatively why not make a one-off donation? All support is appreciated

In a future piece I’ll be publishing an extended essay exploring how and why the SNP are the first populists to blight the UK. Keep your eyes peeled for that coming soon!

Thanks Dean. As ever interesting. There is another view; that a large section of society feels disenfranchised. Our central policy for 30 or 40 years -EU, Integration etc - couldn't generate a majority when asked. This is a warning that something is wrong. That many labour voters don't trust Labour says something is wrong. Your explanation has 2 villains, Farage and more or less "dumb" voters. Is there not a somewhat deeper and better explanation involving shockingly poor connection between our politicos and the people.

Rather that question themselves after the referendum the political class acted like teenagers and blamed others.

As a conservative I see the appeal of Farage but he is symptom of a wider issue.